My Friend Rudy

Rudy and Me

My Friend Rudy

Rudy and Me

Meeting, documenting and eventually becoming friends with WWII Marine Veteran Rudy Matule was one of the great privileges of my working life. He passed away this morning at the age of 99 and we are all better (trust me) for his time with us. Below is the story of some photos and the friendship they created.

I met Rudy in 2004. He was 89. I was 25. At 5 a.m. every day he left his room at the Montana State Veterans Home and went for a 6-mile walk. He told me a few things about the practice that stuck with me.

If you are moving then you know you're alive, so keep moving.

If you 'grease you wheels' (a.k.a exercise) you are gonna feel better, so grease your wheels.

if you can find a friend to walk with it makes the walk better, so find a friend.

Many years prior Rudy's brother had a heart attack. During rehab his doctor told him that he needed to exercise. He didn't want to do it alone, so every day for the next 10 years Rudy walked with his brother. Rudy believed that their daily walks prolonged his brother's life and made them better friends. Our walks did the same for us.

I met Rudy the veterans home whilelooking for a Veterans Day story. I thought maybe I could meet an interesting person to profile for the newspaper I worked at. Inside I quickly met Rudy. He took one look at me and said,

"Yeah I'll let you hang out with me, but you gotta get that hair cut."

Ten minutes later we were at the barbershop and I was getting a 'high and tight' - basically a buzz cut. I got out the chair. Rudy smiled. I laughed. I had new story subject. Rudy had a freshly shorn, young photojournalist.

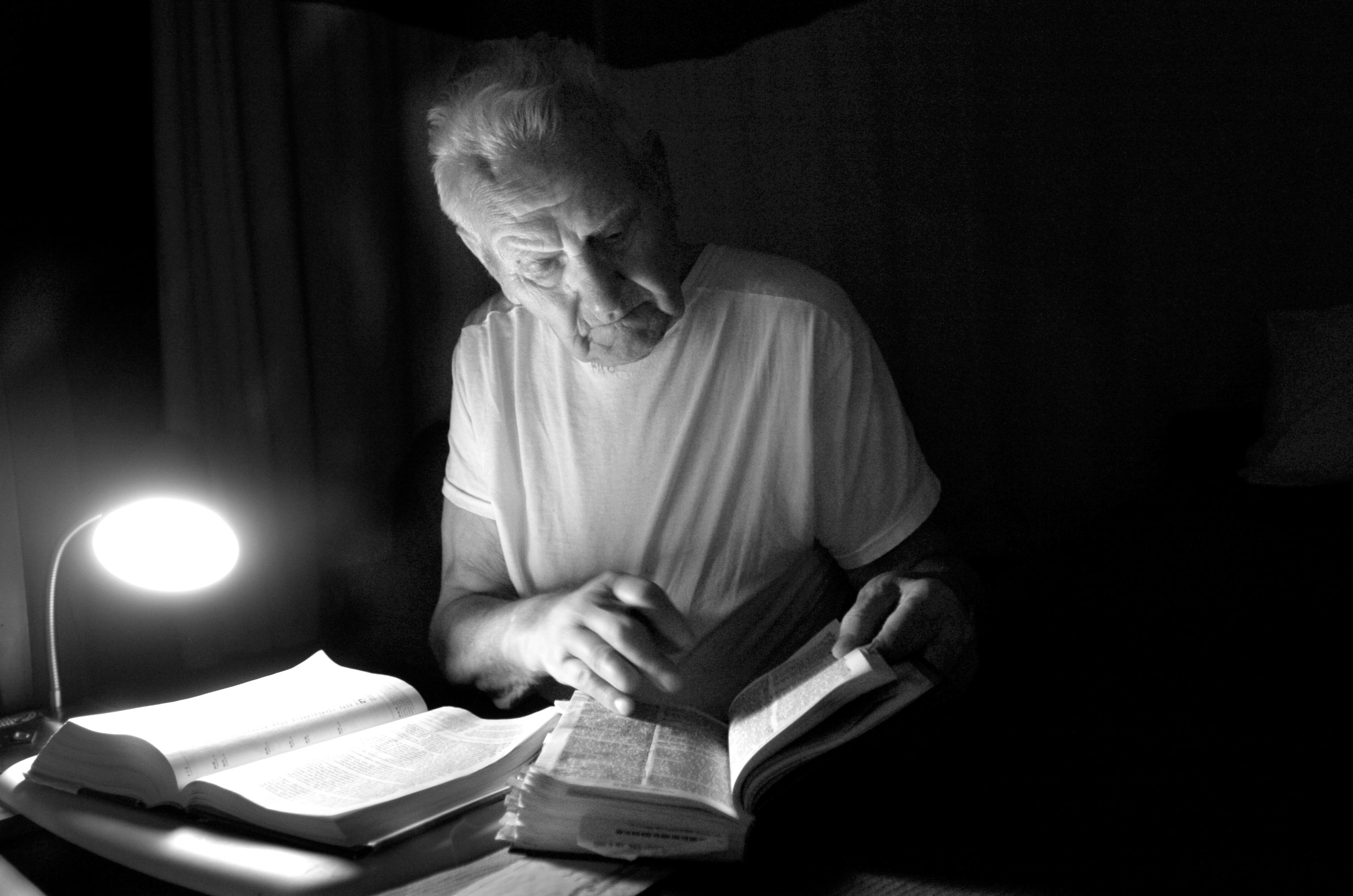

Rudy woke at 2 a.m. every day and read the bible. He told me that the ritual was important to him, so I knew I needed to photograph it. But I had a slight problem. I was keeping fairly late hours at that point, and couldn't figure out if I should photograph the 2 a.m. bible reading before I went to bed or after I woke up. I tried it both ways. I much preferred the super early morning to the sober late night. (Most of my late nights at that point were not sober.)

Ten years later, I see the pictures not only as a document but also as a moment in my growth as a photographer. In my dream world I would have composed this picture a bit differently. I would have liked to give the frame more space and not placed Rudy so dead center. However in order to get this angle I am pinned into the very tight corner of a very small room, so I guess I did the best I could.

More importantly though, I wish the picture had focused on an element of his reading ritual that isn't even in this frame. Rudy's vision was slowly failing and he used a huge magnifying glass to make his way through the pages. I think I was so interested in showing him as a normal, even heroic, person (which he was) that I didn’t want to show him needing a comically large magnifying glass. In hindsight, that would have made the picture more unexpected and interesting. It also would have made Rudy a more complex character when our story was published.

That said, maybe I shouldn’t second-guess it. This picture ended up running pretty big in the paper and Rudy thumbtacked a copy of it to his wall. So even though it could have been different, Rudy liked it enough to put it on the wall - a total honor. Little known fact: bedroom walls and refrigerator doors are prized gallery spaces for newspaper photojournalists.

Rudy was a fan of games and he would often ask me if I wanted to play something. I wasn’t much of a match at his favorite games, bridge and cribbage, so one day we settled for pool. Rudy chalked the cue, I racked the balls, and the veteran playing solitaire in the room with us slowly slumped forward and fell asleep.

"Should I get a nurse?" I asked Rudy.

"No, he's been sleeping a lot lately," he replied.

udy lined up a shot. As he eyed the ball he looked over at me. He said that in a convalescent home you have to keep regular hours and stay awake as much as possible.

“Once you start sleeping, then you start dying,” he told me.

Later that day as Rudy and I went out for a walk we saw the veteran still slumped over, breathing heavily, sleeping. The game of solitaire had not progressed.

Through Rudy I met other vets at the home. Occasionally a few weeks would go by and I wouldn’t see one of his buddies. I would ask Rudy where they were. He would tell me that they were sleeping somewhere. A few weeks later they would be gone. Rudy thought that the slow slip into constant sleep was a sign that you were losing interest in living.

Soon after meeting Rudy I began to wonder about his sleep schedule. I mean the guy got up to read at 2 a.m. then went for a walk 6-mile walk at 5. He must basically sleep all the rest of the day I thought. Nope. On most nights he didn’t go to bed until 9 or 10. Turns out that his life had led him to not need much sleep.

He worked in the Butte, Montana mines as a kid and had to leave his house at 3:30 AM to make his shift. He left the mines to enlisted in the Marines after Pearl Harbor. He fought on four islands in the Pacific including Iwo Jima, which is considered one of the most brutal fights in United States Marine Corps history. He told me that he maybe slept 10 hours during the 31 bloody days of battle on Iwo. After the war he opened a deli and grocery store in Butte and kept his store open from 6 am until 8 p.m. Towards the end of his career as a grocer his wife Helen got sick with Alzheimer's. Rudy cared for her in their home. He told me that he probably didn't sleep more than an hour or two a night for their 13-year long-goodbye.

“Chris, It's like I says,” Rudy told me. " I've had the best life. I've had amazing experiences. I had an incredible family. I mean I've seen the world go from the horse and buggy to the rocket ship to the moon. I am so lucky to be alive. Why would I want to waste any of my time sleeping?"

Rudy’s room was a small space that was split in two by a hospital curtain and shared with gentleman named Andy. Andy kept very different hours from Rudy. He would sleep most of the day and wander the halls of the Veterans Home at night. Rudy was almost the exact opposite.

I spent hours waiting for this photo to happen, in hindsight its not that special, but at the time I felt it was such an important photo to make. I wanted to show how two men who had lived such different lives were now boxed into such small, similar areas. To be honest though, part of my interest in this photo was driven simply by the challenge of finally capturing the illusive moment where they were both in the right spot on either side of the curtain. Either way, I would often stand in this spot, waiting for the photo and one day Rudy asked me what I was doing.

I told Rudy that I thought the photo was important to make because I believed that it was unfair that he had to live in such a small space.

"The room is plenty big Chris," Rudy said. "Plus, the best stuff happens when you leave your room."

In this picture Rudy and some of the other men from home (veterans from WWII , Vietnam and Korea) take a trip to either Wal-Mart or Glacier National Park. I know it was one of them and one of the great things about the Montana State Veterans Home is that it was equidistant from each. There was a limited amount of space on the Vets Home bus, and believe it or not, the Wal-Mart jaunts were prized above the journeys to Glacier.

Rudy attributed this to everyone's need for snacks and underwear.

I was looking back at what I have posted so far and realized that I have shown Rudy to be a solitary figure. He actually was typical of many of us in that he had certain rituals that he pursued in solitude but he also was constantly looking for buddies and folks to share other moments with. Here, he is yucking it up with one of his buddies in the back of the bus. Rudy, constantly the cool-kid, was definitely a back-of-the-bus kind of guy.

One of the things about the vets home and friendship though was that people were old, and eventually they died. All but one of these fellas in this photo are no longer with us.

When you are in your 90s death is part of life. Rudy had seen many of his friends die in the war. He lost his daughter when she was 18. His wife had died. He was one of 12 children and was the last one left. So death in the home was not as hard as the other losses he had faced. He told me that seeing your friends and family die was, by far, the hardest thing about growing old.

Rudy once told me that experiencing others' death is a way to appreciate being alive and preparing for your own death. ‘Chris it’s like I says - I want to stay as long as I can, but when the time comes I’ll be ready,’ he told me.

I love the beautiful optimism in this sentiment. Even in death we feel gratitude and we learn.

When the story ran in the paper I didn’t have a photo of Rudy that said “heroic veteran.” Usually the most obvious element of a story is easy to photograph, but with Rudy I struggled to visually show his past sacrifice and service.

I had a photograph of his hand pointing out the various islands where his division fought - Roi Namur, Saipan, Tinian, and Iwo Jima. On Iwo his battalion was battling through a valley below Mt Suribachi when the famous flag-raising moment happened. He stood up and cheered as the flag went up. Then he jumped to the ground as bullets flew past his face. With bullets overhead and his face pressed into the dirt, Rudy could hear Japanese soldiers running in the tunnels underneath him.

Rudy said life on Iwo was a constant stream of being scared shitless one minute, laughing really hard when a friend would crack a joke the next, standing up and running into a hail of bullets the next. This process was repeated all day, day after day, for 36 days. Iwo is considered one of the most vicious fights in American history. It gave us the phrase “where uncommon valor was a common virtue.”

Rudy returned with the understanding that soldiers shouldn't talk about what they had experienced. Now, in his 90s, Rudy decided to open up. He shared honestly. I listened intently. We bonded. I learned that the photograph of the hand on the page wasn’t enough.

I went to vote with him to show what he had fought for. I photographed him smiling broadly after casting his vote for John Kerry. Rudy hated Bush.

“No one who hasn’t been to war should be allowed to send us to war,” Rudy said.

I mentioned that by this logic war might stop. Rudy said he wasn’t a pacifist. He relished his identity as a soldier. “But there’s gotta be a better way,” he said. “So many of my friends died.”

After the story was published, Rudy was asked to raise the Marine flag on Memorial Day. He was honored. After he raised the flag he saluted and stood in this position for almost a full minute. Rather than discomfort, I think people grew more somber and more appreciative of service the longer Rudy held the pose – thanking his friends.

As I mentioned in my last post, I was still hanging out with Rudy after the story ran in the paper. There was part of me that wanted to nail the 'heroic veteran' photo, but something else was happening — we were becoming friends.

We transitioned pretty smoothly from journalist and subject to buddies. We played Keno, we went for walks, and we ate a lot of breakfasts. I was living in the same town with my folks, and at some point, as you do with your friends, I wanted to introduce my parents to Rudy. So I invited my folks to the Memorial Day ceremony, and here they are meeting. Rudy is hugging is my mom, and that's my dad smiling behind Rudy.

Rudy became fast friends with my parents. Then he became friends with their friends. He started having beers with my dad’s buddy Dave and going to meals with our family friend Joey. He was at holiday dinners and summer picnics. He became part of our family.

About a year before I met Rudy, my mother’s father died. Grandpa Bud was funny, wise and so, so kind. I think having Rudy around gave my family access to the kindness and wisdom of a generation that we had lost. For that, and so much more, I will forever be grateful.

Rudy,

When you passed away last week I wasn't ready to say goodbye, so I went into my photo archive and relived our time together. Soon I was smiling and laughing and editing and writing. Sharing these photos and stories has been my way to say thank you. You are a special man who became a meaningful part of my community. Even though you physically won't be with us around the dinner table at our next holiday occasion I believe that your spirit of kindness, humor and caring will live on with, and through, all of the people you touched. So goodbye Rudy. Thank you. I love you.

Chris